The Philippines was once under the colonial rule of the United States by virtue of the Commonwealth. After the Commonwealth, the Philippines was on its own but the American influence lived on.

The Philippines was once under the colonial rule of the United States by virtue of the Commonwealth. After the Commonwealth, the Philippines was on its own but the American influence lived on.

In the legal system, American influence is evident on how American jurisprudence has helped enrich the Philippine legal system. One doctrine we adopted was the Miranda Rights.

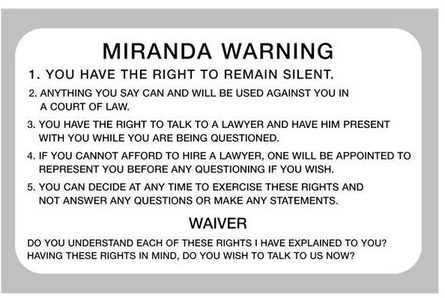

The Philippine version of the Miranda Doctrine basically provides that:

1. A person in custody must be informed at the outset in clear and unequivocal terms that he has the right to remain silent; and that anything he says can and will be used against him in a court of law;

2. He has the right to an attorney and if he can’t secure one, a lawyer shall be appointed to represent him. His right to counsel is available at any stage of the interrogation even if he initially consents to giving any information without the assistance of counsel.

If the above is not observed, it renders all evidence obtained therefrom to be inadmissible in court, being the “fruit of a poisonous tree.” It is therefore imperative that these rights are read to the person in custody prior to being subjected to questioning.

Now it is an established rule that the Miranda Doctrine does not have to be read out in every arrest being made by police officers. It is however a must that if the person is already taken into police custody and the police carries out a process of interrogation upon the person arrested in custody and he is already being asked incriminating questions, his Miranda Rights must be read him.

But are there other instances when the a person arrested is not read his Miranda Rights?

Recently in America, the surviving suspect of the Boston Marathon bombing was taken into custody without the cops reading him his rights. CNN commentators went abuzz about the lack of it but then the police officers issued a statement which provided the reason why he was not read his (Dzhokhar Tsarnaev) rights upon arrest was that they are going to be using the so called “Public Safety Clause” (PSC).

The PSC is an exception to the Miranda Doctrine whereby a person may be subjected to questioning even without being read his rights. The rationale behind this exception is that, it is of the essence that the person should be interrogated immediately and information be obtained from him because of the exigent circumstances attendant to the case. In the case of Tsarnaev, the Federal Bureau of Investigation found it necessary to obtain uncounseled information from Tsarnaev regarding the existence of other unexploded bombs, which, if any, needed to be found immediately for the protection of public safety.

As a consequence, the information obtained from Tsarnaev under the PSC can and may be used against him in court even if he was not read his rights. But this does not mean that the Miranda Right can be dispensed with, the person should still be read his rights if there are other questions needed to be asked which are no longer covered by the PSC.

In the Philippine setting, is the PSC applicable?

The PSC is a doctrine emphasized in the case of New York vs. Quarles (467 US 649), a 1984 US case. Obviously, this case has no legal authority over cases in the Philippines for it was decreed long after the American occupation. But it can be adapted and localized considering our ever evolving legal system.

It may already have an equivalent, namely, the Exigent Circumstances Doctrine (ECD). This doctrine though is commonly used in warrantless arrest and warrantless search and seizure cases. I am yet to see one involving Miranda Doctrine. (So if you have read one please comment it out below!)

The ECD basically provides that the normal procedures and rules of court in the admissibility of evidence may be disregarded in exigent circumstances like when there is a coup d’ etat. The rationale is the same as with PSC, that is to protect public safety or national security. This doctrine was used in the 1994 case of People vs Rolando De Gracia (GR Nos. 102009-10). The accused therein was subjected to a warrantless search and seizure sometime in 1989 during the height of the coup attempts against then President Cory Aquino. Confiscated from him were various explosives and ammunition. De Gracia contested the warrantless search and seizure but the Supreme Court ruled that the search warrant can be dispensed with due to the exigent circumstances attendant to the case.

This case still stands unchallenged jurisprudence-wise.

However, in 2007, the Human Security Act was passed. This law defines what terrorism is (as applied to Philippine settings). Under this law, rebellion, insurrection, and coup d’ etat and several other crimes committed to sow and create a widespread and extraordinary fear and panic among the populace, in order to coerce the government to give in to an unlawful demand is classified as terrorism.

Now under Section 21 of this law, any person apprehended pursuant to this law shall be Mirandized. Nowhere in the law does it state that there are exceptions. The question now is, is the De Gracia case still considered good law? Or is it superseded by the silence of the Human Security Act? (Maybe I did miss some case directly tackling this issue so feel free to comment below. Let’s learn together!)

DISCLAIMER: The author is just a law student. This is not a legal advice nor should it be taken as an authoritative interpretation/statement of the law. This article was written according to the author’s research and understanding of the law involved. This is meant to espouse academic discussion and initiate a better understanding of the law. Feel free to leave your comment/s, criticism/s, and/or suggestion/s below.